Pushtoday

MuscleChemistry Registered Member

Scofield, Dennis E. MAEd, CSCS; Kardouni, Joseph R. DPT, PhD

The term “tactical athlete” is commonly used by those in the tactical strength and conditioning community to identify personnel in law enforcement, military, and rescue professions who require unique physical training strategies aimed at optimizing occupational physical performance. Although the term tactical athlete and respective programs directed at improving tactical physical performance began as early as 2005 (Table 1), there may be ambiguity in the term tactical athlete for those unfamiliar with this subject area. Therefore, it is important to provide the rationale and context of this term because it is frequently used by professionals in the fields of human performance, injury prevention, healthcare, and health sciences who work with this population. It is also important to describe the term tactical athlete so that those who read human performance and medical literature understand the term, especially if they do not regularly interact with personnel whose occupations lead them to be classified as tactical athletes. The purpose of this article is to promote awareness and provide rationale for use of the term tactical athlete.

WHO IS AN ATHLETE?

The term athlete is often thought of as being synonymous with someone who participates in a competition or contest that requires a certain level of physical fitness and skill. The word athlete comes from the ancient Greek word “āthlētēs” which means contestant ([SUP]1[/SUP]). By definition, an athlete is “a person trained or gifted in exercises or contests involving physical agility, coordination, stamina, or strength” ([SUP]17[/SUP]). Considering the broad context for which an athlete is defined, it is conceivable that athlete demographics are as diverse as the sports in which they compete. The one common tie among most athletes regardless of age or sport is the requirement of general physical preparedness (GPP), on which the technical and tactical skills (T/TSs) requisite for the sport or competition are developed ([SUP]2,11,15[/SUP]). GPP can be described as an all-encompassing state of physical fitness whereby cardiorespiratory endurance, anaerobic endurance, muscle strength, power, flexibility, and mobility are developed and maintained. It is the foundation on which T/TSs specific to the sport are further developed and deployed ([SUP]13[/SUP]). These skills are necessary to perform both the specific movements (technical aspects) associated with a sport and the ability to analyze and deploy these skills to overcome a physical challenge/obstacle or outperform an opponent (tactical aspects) ([SUP]3[/SUP]). For example, in most team and combat sports (e.g., football, basketball, soccer, and wrestling) GPP is a prerequisite for building further on technical and tactical aspects of the sport, such as blocking and evading, footwork, grappling, or agility. Some events, such as endurance sports and track and field, are more heavily weighted toward GPP, with less emphasis on T/TSs, although movement techniques are required to maximize efficiency, power, and speed. Although the dimension of physical performance in athletics is well accepted and understood, many physically demanding occupations require personnel to develop GPP and T/TS that are crucial in environments involving civil protection, grave physical danger, hostile forces, or rescue situations.

DEFINING THE TACTICAL ATHLETE

Tactical professionals working in military, law enforcement, firefighting, and rescue professions require expertise in their occupational skills concomitant with GPP, which enables them to perform physically demanding occupational tasks while mitigating injury ([SUP]7[/SUP]). Tactical professionals, like traditional athletes, require both a level of fitness and T/TSs commensurate with their occupational requirements to successfully achieve short-term objectives and overcome various threats (human or environmental) ([SUP]6,10,14,21[/SUP]). The heavy reliance on physical fitness is such that recruitment and initial training of military, law enforcement, and fire-service professionals is graded on demonstrable fitness standards requisite for selection or graduation from initial training schools ([SUP]4,5,8,24[/SUP]). Moreover, initial training often requires recruits/candidates to adapt to strenuous physical and mental conditioning for sustained durations lasting weeks or months ([SUP]22[/SUP]).

At the completion of initial training, recruits/candidates are required to possess the physical and mental preparedness necessary to effectively operate in their occupation, a foundation on which further development of occupational T/TS will be developed ([SUP]16,18,19[/SUP]). For military personnel, further development of T/TS may include skills, such as airborne training, water survival, reconnaissance training, or hand-to-hand combat. Law enforcement professions may require advanced training in emergency response or special weapons and tactics training among other specialized courses that may require development of specific fitness components (strength, power, agility, etc.) that contribute to optimizing occupational performance. In addition, firefighters may pursue training in victim extraction, jump and survival, and tactical first-response law enforcement, all of which require candidates to meet physical fitness standards. Collectively, there is a common requirement among tactical professionals to exceed a minimum threshold of fitness and to further develop specific components of fitness (e.g., power, muscle endurance, mobility) enabling them to successfully execute T/TSs.

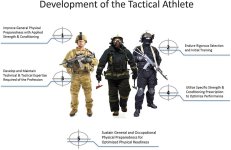

When developing strength and conditioning programs aimed at improving occupational physical performance, strength and conditioning professionals often use principles, such as progression, overload, and specificity to strategically periodize training cycles. Additional considerations should include the training status/training phase of the tactical athlete; continual evaluation of these can provide insight on recovery status and outcome goals (Figure). Like traditional athletes, properly designed strength and conditioning programs are crucial for optimizing physical preparedness in tactical athletes. Lack or deterioration of GPP and T/TS as a result of a poorly designed physical training program, or no physical training, incurs similar results in both groups—early fatigue, a higher likelihood of injury, defeat, or in some cases death ([SUP]9,12,20,23[/SUP]). However, one noted difference between tactical and traditional athletes is that tactical athletes have no scheduled start or end to an event. For many tactical athletes, call to duty, reaction, and response to events can occur at any time; as such tactical athletes must always be prepared for deployment to situations that present ongoing physical and mental stressors that last for unknown durations of time.

Front line tactical personnel whose line of duty requirements include running, climbing, swimming, or traversing austere and rugged environments can understandably be classified as tactical athletes. However, it could be argued that some personnel within tactical organizations perform primarily administrative or domestic duties and do not typically rely on GPP. While there are duties or jobs within tactical organizations that do not routinely require feats of athleticism, we cannot discount the fact that tactical personnel are most often required to meet standards of physical fitness established by their professional organizations. In addition, personnel in tactical organizations may unexpectedly find themselves in situations where they must rely on the GPP and T/TS to conduct rescue operations or react to an environmental or human threat. To offer an example, examine this from the perspective of a military personnel clerk. On a daily basis, the clerk performs administrative duties typical of many civilian office workers. However, the clerk is still required to exceed the minimum standard of physical fitness expected by the military. To ensure this, the military tests physical fitness semiannually and units require weekly or daily participation in physical training. There is also the potential that a military personnel clerk will participate in military field training or deploy to a hazardous environment where reacting to incoming fire, participating in installation security, or rendering aid to injured or endangered comrades is required. This example highlights the fact that regardless of occupational specialty, there is a potential for unexpected physically stressful situations to arise where a lack of physical preparedness could pose a serious liability.

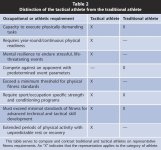

There are several descriptions of traditional athletes that are commonly used depending on the level of commitment or participation in physical activity or sports. The level of commitment to training or level of competition is used to broadly classify athletes into categories, such as recreational, competitive, amateur, or professional. Athletes who comprise any of these categories are diverse in their level of physical fitness, sport-specific skill sets, and occupations. Their lifestyles and occupations range from mostly sedentary to very active, and there is generally a clear distinction to which category they fall into. When considering their activity-specific training and health care needs, we still classify these individuals as athletes. Similarly, tactical athletes often have physical fitness standards, with diverse frequency, duration, type, and intensity of physical exertion associated with their occupational specialty within their tactical organization. Therefore, it is appropriate to classify personnel in tactical occupations broadly as tactical athletes, while recognizing that, similar to traditional athletes, there may be varying levels of tactical proficiency training or physical and psychological demands across occupations that result in different strata for tactical athletes. The commonality among tactical athletes becomes the explicit requirement of baseline physical fitness, with the potential occupational requirement of confronting and overcoming physical, environmental, and human threats with little to no advanced notice. This underscores the importance of maintaining GPP due to the variability and unpredictability of threats and emergencies encountered by tactical athletes. Another contrast between tactical and traditional athletes is that field operations and emergencies can limit opportunities for physical and psychological recovery. During line of duty operations, tactical athletes may have to endure inadequate sleep superimposed on suboptimal nutrition, with limited or no access to recovery modalities, such as massage, hydrotherapy, ice, etc. There are significant differences in psychological health requirements between tactical and traditional athletes as well. Tactical athletes may be required to make extremely difficult (life or death) decisions during high tempo environments that are physically and mentally stressful, which is an extremely rare occurrence in traditional sports. Some key distinctions between tactical and traditional athletes are found in Table 2. There are numerous physically demanding occupations, but the differentiating factor for classifying individuals as tactical athletes is the occupational requirement of providing a tactical response to a physically threatening or emergent situation that may arise without notice and last for an unpredictable duration of time.

EMERGENCE OF TRAINING PROGRAMS FOR TACTICAL ATHLETES

Within the last decade, the term tactical athlete has been used by several organizations, fitness programs, and Web sites to define professionals who rely on novel, occupation specific, strength and conditioning strategies as a means to enhance physical performance in their respective profession. The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA), the U.S. military, and several universities have developed programs to improve physical training methodologies used by tactical units, often drawing from strategies used by collegiate athletic training and strength and conditioning programs. A brief overview of the various organizations and commercial entities that have developed physical training methodologies incorporating emerging best practices in strength and conditioning and injury rehabilitation and mitigation can be found in Table 1. An example of this paradigm shift can be found by examining recent changes in U.S. Army physical training. In 2010, the U.S. Army launched the Soldier Athlete Initiative. Spearheaded by Lieutenant General (Retired) Mark Hertling, who was the Deputy Commander of Initial Military Training at the time, the initiative sought to improve physical performance among initial entry soldiers by upgrading physical training, injury mitigation strategies, and nutrition to reflect that of collegiate athletic programs. This was a significant move for the U.S. Army, since physical training and testing had changed little since 1980. The Soldier Athlete Initiative recognized that soldiers are tactical athletes, and as such their physical training should encompass more than push-ups, sit-ups, and endurance runs. A gradual overhaul of the way the U.S. Army conducted physical training led to the addition of strength, power, agility, core, and endurance training to effectively prepare soldiers for the physical demands of full-spectrum operations.

SUMMARY

The term tactical athlete is popularly used to categorize personnel working in tactical professions. This is due to the fact that, like traditional athletes, tactical athletes rely on GPP and T/TS for achieving successful and effective operational outcomes. The last decade has fostered awareness that tactical professionals benefit from using strength and conditioning strategies that have been used by traditional athletes to improve athletic performance. However, for the tactical athlete there is no off-season. Tactical athletes are expected to effectively respond to a myriad of unpredictable, physically and psychologically stressful events; tasks only accomplished by continual physical readiness. In other words, tactical athletes are always operating “in-season.”

The emergence of the tactical athlete has been driven by knowledge and principles imparted by ongoing research in strength and conditioning. Novel physical training strategies that improve a tactical athlete's ability to react and mitigate threats and emergencies are developed from methodologies similarly used for traditional athletes. The NSCA has devoted research and education resources toward the development of physical training guidelines aimed at optimizing tactical physical performance and injury mitigation. This has been the impetus to identifying another class of athlete—the tactical athlete. As strength and conditioning research continues, so will the evolution of effective physical training strategies. This will benefit both the traditional and tactical athlete, whose physical preparedness is of paramount importance.

[h=4]REFERENCES[/h]

1. American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2011. Available at: http://www.thefreedictionary.com/athlete. Accessed January 8, 2015.Cited Here...

2. Cann AP, Vandervoort AA, Lindsay DM. Optimizing the benefits versus risks of golf participation by older people. J Geriatr Phys Ther 28: 85–92, 2005.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

3. Halouani J, Chtourou H, Gabbett T, Chaouachi A, Chamari K. Small-sided games in team sports training: A brief review. J Strength Cond Res 28: 3594–3618, 2014.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

4. Henning PC, Khamoui AV, Brown LE. Preparatory strength and endurance training for U.S. Army basic combat training. Strength Cond J 33: 48–57, 2011. 10.1519/SSC.1510b1013e31822fdb31822e.Cited Here...

5. Jamnik V, Gumienak R, Gledhill N. Developing legally defensible physiological employment standards for prominent physically demanding public safety occupations: A Canadian perspective. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 2447–2457, 2013.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

6. Jette M, Kimick A, Sidney K. Evaluating the occupational physical fitness of Canadian forces infantry personnel. Mil Med 154: 318–322, 1989.Cited Here... | PubMed

7. Kechijian D, Rush S. Tactical physical preparation: The case for a movement-based approach. J Spec Oper Med 12: 43–49, 2012.Cited Here...

8. Knapik JJ, Darakjy S, Hauret KG, Canada S, Scott S, Rieger W, Marin R, Jones BH. Increasing the physical fitness of low-fit recruits before basic combat training: An evaluation of fitness, injuries, and training outcomes. Mil Med 171: 45–54, 2006.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

9. Knapik JJ, Grier T, Spiess A, Swedler DI, Hauret KG, Graham B, Yoder J, Jones BH. Injury rates and injury risk factors among Federal Bureau of Investigation new agent trainees. BMC Public Health 11: 920, 2011.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

10. McDaniel LA. A Concept for Functional Fitness, 2006. Available at:http://www.marines.mil/News/Message...-the-usmc-concept-for-functional-fitness.aspx. Accessed January 5, 2015.Cited Here...

11. Milanovic Z, Sporis G, Trajkovic N, James N, Samija K. Effects of a 12 week SAQ training programme on agility with and without the ball among young soccer players. J Sports Sci Med 12: 97–103, 2013.Cited Here...

12. Nindl BC, Williams TJ, Deuster PA, Butler NL, Jones BH. Strategies for optimizing military physical readiness and preventing musculoskeletal injuries in the 21st century. US Army Med Dep J Oct-Dec: 5–23, 2013.Cited Here...

13. Padulo J, Chamari K, Chaabene H, Ruscello B, Maurino L, Sylos Labini P, Migliaccio GM. The effects of one-week training camp on motor skills in Karate kids. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 54: 715–724, 2014.Cited Here... | PubMed

14. Pawlak R, Clasey J, Palmer T, Symons B, Abel MG. The effect of a novel tactical training program on physical fitness and occupational performance in firefighters. J Strength Cond Res 29: 578–588, 2015.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

15. Petersen C. Pre-season tennis conditioning. Can Fam Physician 34: 141–145, 1988.Cited Here... | PubMed

16. Phillips M, Petersen A, Abbiss CR, Netto K, Payne W, Nichols D, Aisbett B. Pack hike test finishing time for Australian firefighters: Pass rates and correlates of performance. Appl Ergon 42: 411–418, 2011.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

17. Random House Inc. Random House Kernerman Webster's College Dictionary. Random House Inc, 2010. Available at: http://www.thefreedictionary.com/athlete. Accessed January 8, 2015.Cited Here...

18. Sell TC, Abt JP, Crawford K, Lovalekar M, Nagai T, Deluzio JB, Smalley BW, McGrail MA, Rowe RS, Cardin S, Lephart SM. Warrior Model for Human Performance and Injury Prevention: Eagle Tactical Athlete Program (ETAP) Part I. J Spec Oper Med 10: 2–21, 2010.Cited Here...

19. Sell TC, Abt JP, Crawford K, Lovalekar M, Nagai T, Deluzio JB, Smalley BW, McGrail MA, Rowe RS, Cardin S, Lephart SM. Warrior Model for Human Performance and Injury Prevention: Eagle Tactical Athlete Program (ETAP) Part II. J Spec Oper Med 10: 22–33, 2010.Cited Here...

20. Smith DL. Firefighter fitness: Improving performance and preventing injuries and fatalities. Curr Sports Med Rep 10: 167–172, 2011.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

21. Sothmann MS, Gebhardt DL, Baker TA, Kastello GM, Sheppard VA. Performance requirements of physically strenuous occupations: Validating minimum standards for muscular strength and endurance. Ergonomics 47: 864–875, 2004.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

22. Stamford BA, Weltman A, Moffatt RJ, Fulco C. Status of police officers with regard to selected cardio-respiratory and body compositional fitness variables. Med Sci Sports 10: 294–297, 1978.Cited Here... | PubMed

23. Storer TW, Dolezal BA, Abrazado ML, Smith DL, Batalin MA, Tseng CH, Cooper CB. Firefighter health and fitness assessment: A call to action. J Strength Cond Res 28: 661–671, 2014.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

24. Wynn P, Hawdon P. Cardiorespiratory fitness selection standard and occupational outcomes in trainee firefighters. Occup Med (Lond) 62: 123–128, 2012.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

The term “tactical athlete” is commonly used by those in the tactical strength and conditioning community to identify personnel in law enforcement, military, and rescue professions who require unique physical training strategies aimed at optimizing occupational physical performance. Although the term tactical athlete and respective programs directed at improving tactical physical performance began as early as 2005 (Table 1), there may be ambiguity in the term tactical athlete for those unfamiliar with this subject area. Therefore, it is important to provide the rationale and context of this term because it is frequently used by professionals in the fields of human performance, injury prevention, healthcare, and health sciences who work with this population. It is also important to describe the term tactical athlete so that those who read human performance and medical literature understand the term, especially if they do not regularly interact with personnel whose occupations lead them to be classified as tactical athletes. The purpose of this article is to promote awareness and provide rationale for use of the term tactical athlete.

WHO IS AN ATHLETE?

The term athlete is often thought of as being synonymous with someone who participates in a competition or contest that requires a certain level of physical fitness and skill. The word athlete comes from the ancient Greek word “āthlētēs” which means contestant ([SUP]1[/SUP]). By definition, an athlete is “a person trained or gifted in exercises or contests involving physical agility, coordination, stamina, or strength” ([SUP]17[/SUP]). Considering the broad context for which an athlete is defined, it is conceivable that athlete demographics are as diverse as the sports in which they compete. The one common tie among most athletes regardless of age or sport is the requirement of general physical preparedness (GPP), on which the technical and tactical skills (T/TSs) requisite for the sport or competition are developed ([SUP]2,11,15[/SUP]). GPP can be described as an all-encompassing state of physical fitness whereby cardiorespiratory endurance, anaerobic endurance, muscle strength, power, flexibility, and mobility are developed and maintained. It is the foundation on which T/TSs specific to the sport are further developed and deployed ([SUP]13[/SUP]). These skills are necessary to perform both the specific movements (technical aspects) associated with a sport and the ability to analyze and deploy these skills to overcome a physical challenge/obstacle or outperform an opponent (tactical aspects) ([SUP]3[/SUP]). For example, in most team and combat sports (e.g., football, basketball, soccer, and wrestling) GPP is a prerequisite for building further on technical and tactical aspects of the sport, such as blocking and evading, footwork, grappling, or agility. Some events, such as endurance sports and track and field, are more heavily weighted toward GPP, with less emphasis on T/TSs, although movement techniques are required to maximize efficiency, power, and speed. Although the dimension of physical performance in athletics is well accepted and understood, many physically demanding occupations require personnel to develop GPP and T/TS that are crucial in environments involving civil protection, grave physical danger, hostile forces, or rescue situations.

DEFINING THE TACTICAL ATHLETE

Tactical professionals working in military, law enforcement, firefighting, and rescue professions require expertise in their occupational skills concomitant with GPP, which enables them to perform physically demanding occupational tasks while mitigating injury ([SUP]7[/SUP]). Tactical professionals, like traditional athletes, require both a level of fitness and T/TSs commensurate with their occupational requirements to successfully achieve short-term objectives and overcome various threats (human or environmental) ([SUP]6,10,14,21[/SUP]). The heavy reliance on physical fitness is such that recruitment and initial training of military, law enforcement, and fire-service professionals is graded on demonstrable fitness standards requisite for selection or graduation from initial training schools ([SUP]4,5,8,24[/SUP]). Moreover, initial training often requires recruits/candidates to adapt to strenuous physical and mental conditioning for sustained durations lasting weeks or months ([SUP]22[/SUP]).

At the completion of initial training, recruits/candidates are required to possess the physical and mental preparedness necessary to effectively operate in their occupation, a foundation on which further development of occupational T/TS will be developed ([SUP]16,18,19[/SUP]). For military personnel, further development of T/TS may include skills, such as airborne training, water survival, reconnaissance training, or hand-to-hand combat. Law enforcement professions may require advanced training in emergency response or special weapons and tactics training among other specialized courses that may require development of specific fitness components (strength, power, agility, etc.) that contribute to optimizing occupational performance. In addition, firefighters may pursue training in victim extraction, jump and survival, and tactical first-response law enforcement, all of which require candidates to meet physical fitness standards. Collectively, there is a common requirement among tactical professionals to exceed a minimum threshold of fitness and to further develop specific components of fitness (e.g., power, muscle endurance, mobility) enabling them to successfully execute T/TSs.

When developing strength and conditioning programs aimed at improving occupational physical performance, strength and conditioning professionals often use principles, such as progression, overload, and specificity to strategically periodize training cycles. Additional considerations should include the training status/training phase of the tactical athlete; continual evaluation of these can provide insight on recovery status and outcome goals (Figure). Like traditional athletes, properly designed strength and conditioning programs are crucial for optimizing physical preparedness in tactical athletes. Lack or deterioration of GPP and T/TS as a result of a poorly designed physical training program, or no physical training, incurs similar results in both groups—early fatigue, a higher likelihood of injury, defeat, or in some cases death ([SUP]9,12,20,23[/SUP]). However, one noted difference between tactical and traditional athletes is that tactical athletes have no scheduled start or end to an event. For many tactical athletes, call to duty, reaction, and response to events can occur at any time; as such tactical athletes must always be prepared for deployment to situations that present ongoing physical and mental stressors that last for unknown durations of time.

Front line tactical personnel whose line of duty requirements include running, climbing, swimming, or traversing austere and rugged environments can understandably be classified as tactical athletes. However, it could be argued that some personnel within tactical organizations perform primarily administrative or domestic duties and do not typically rely on GPP. While there are duties or jobs within tactical organizations that do not routinely require feats of athleticism, we cannot discount the fact that tactical personnel are most often required to meet standards of physical fitness established by their professional organizations. In addition, personnel in tactical organizations may unexpectedly find themselves in situations where they must rely on the GPP and T/TS to conduct rescue operations or react to an environmental or human threat. To offer an example, examine this from the perspective of a military personnel clerk. On a daily basis, the clerk performs administrative duties typical of many civilian office workers. However, the clerk is still required to exceed the minimum standard of physical fitness expected by the military. To ensure this, the military tests physical fitness semiannually and units require weekly or daily participation in physical training. There is also the potential that a military personnel clerk will participate in military field training or deploy to a hazardous environment where reacting to incoming fire, participating in installation security, or rendering aid to injured or endangered comrades is required. This example highlights the fact that regardless of occupational specialty, there is a potential for unexpected physically stressful situations to arise where a lack of physical preparedness could pose a serious liability.

There are several descriptions of traditional athletes that are commonly used depending on the level of commitment or participation in physical activity or sports. The level of commitment to training or level of competition is used to broadly classify athletes into categories, such as recreational, competitive, amateur, or professional. Athletes who comprise any of these categories are diverse in their level of physical fitness, sport-specific skill sets, and occupations. Their lifestyles and occupations range from mostly sedentary to very active, and there is generally a clear distinction to which category they fall into. When considering their activity-specific training and health care needs, we still classify these individuals as athletes. Similarly, tactical athletes often have physical fitness standards, with diverse frequency, duration, type, and intensity of physical exertion associated with their occupational specialty within their tactical organization. Therefore, it is appropriate to classify personnel in tactical occupations broadly as tactical athletes, while recognizing that, similar to traditional athletes, there may be varying levels of tactical proficiency training or physical and psychological demands across occupations that result in different strata for tactical athletes. The commonality among tactical athletes becomes the explicit requirement of baseline physical fitness, with the potential occupational requirement of confronting and overcoming physical, environmental, and human threats with little to no advanced notice. This underscores the importance of maintaining GPP due to the variability and unpredictability of threats and emergencies encountered by tactical athletes. Another contrast between tactical and traditional athletes is that field operations and emergencies can limit opportunities for physical and psychological recovery. During line of duty operations, tactical athletes may have to endure inadequate sleep superimposed on suboptimal nutrition, with limited or no access to recovery modalities, such as massage, hydrotherapy, ice, etc. There are significant differences in psychological health requirements between tactical and traditional athletes as well. Tactical athletes may be required to make extremely difficult (life or death) decisions during high tempo environments that are physically and mentally stressful, which is an extremely rare occurrence in traditional sports. Some key distinctions between tactical and traditional athletes are found in Table 2. There are numerous physically demanding occupations, but the differentiating factor for classifying individuals as tactical athletes is the occupational requirement of providing a tactical response to a physically threatening or emergent situation that may arise without notice and last for an unpredictable duration of time.

EMERGENCE OF TRAINING PROGRAMS FOR TACTICAL ATHLETES

Within the last decade, the term tactical athlete has been used by several organizations, fitness programs, and Web sites to define professionals who rely on novel, occupation specific, strength and conditioning strategies as a means to enhance physical performance in their respective profession. The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA), the U.S. military, and several universities have developed programs to improve physical training methodologies used by tactical units, often drawing from strategies used by collegiate athletic training and strength and conditioning programs. A brief overview of the various organizations and commercial entities that have developed physical training methodologies incorporating emerging best practices in strength and conditioning and injury rehabilitation and mitigation can be found in Table 1. An example of this paradigm shift can be found by examining recent changes in U.S. Army physical training. In 2010, the U.S. Army launched the Soldier Athlete Initiative. Spearheaded by Lieutenant General (Retired) Mark Hertling, who was the Deputy Commander of Initial Military Training at the time, the initiative sought to improve physical performance among initial entry soldiers by upgrading physical training, injury mitigation strategies, and nutrition to reflect that of collegiate athletic programs. This was a significant move for the U.S. Army, since physical training and testing had changed little since 1980. The Soldier Athlete Initiative recognized that soldiers are tactical athletes, and as such their physical training should encompass more than push-ups, sit-ups, and endurance runs. A gradual overhaul of the way the U.S. Army conducted physical training led to the addition of strength, power, agility, core, and endurance training to effectively prepare soldiers for the physical demands of full-spectrum operations.

SUMMARY

The term tactical athlete is popularly used to categorize personnel working in tactical professions. This is due to the fact that, like traditional athletes, tactical athletes rely on GPP and T/TS for achieving successful and effective operational outcomes. The last decade has fostered awareness that tactical professionals benefit from using strength and conditioning strategies that have been used by traditional athletes to improve athletic performance. However, for the tactical athlete there is no off-season. Tactical athletes are expected to effectively respond to a myriad of unpredictable, physically and psychologically stressful events; tasks only accomplished by continual physical readiness. In other words, tactical athletes are always operating “in-season.”

The emergence of the tactical athlete has been driven by knowledge and principles imparted by ongoing research in strength and conditioning. Novel physical training strategies that improve a tactical athlete's ability to react and mitigate threats and emergencies are developed from methodologies similarly used for traditional athletes. The NSCA has devoted research and education resources toward the development of physical training guidelines aimed at optimizing tactical physical performance and injury mitigation. This has been the impetus to identifying another class of athlete—the tactical athlete. As strength and conditioning research continues, so will the evolution of effective physical training strategies. This will benefit both the traditional and tactical athlete, whose physical preparedness is of paramount importance.

[h=4]REFERENCES[/h]

1. American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2011. Available at: http://www.thefreedictionary.com/athlete. Accessed January 8, 2015.Cited Here...

2. Cann AP, Vandervoort AA, Lindsay DM. Optimizing the benefits versus risks of golf participation by older people. J Geriatr Phys Ther 28: 85–92, 2005.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

3. Halouani J, Chtourou H, Gabbett T, Chaouachi A, Chamari K. Small-sided games in team sports training: A brief review. J Strength Cond Res 28: 3594–3618, 2014.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

4. Henning PC, Khamoui AV, Brown LE. Preparatory strength and endurance training for U.S. Army basic combat training. Strength Cond J 33: 48–57, 2011. 10.1519/SSC.1510b1013e31822fdb31822e.Cited Here...

5. Jamnik V, Gumienak R, Gledhill N. Developing legally defensible physiological employment standards for prominent physically demanding public safety occupations: A Canadian perspective. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 2447–2457, 2013.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

6. Jette M, Kimick A, Sidney K. Evaluating the occupational physical fitness of Canadian forces infantry personnel. Mil Med 154: 318–322, 1989.Cited Here... | PubMed

7. Kechijian D, Rush S. Tactical physical preparation: The case for a movement-based approach. J Spec Oper Med 12: 43–49, 2012.Cited Here...

8. Knapik JJ, Darakjy S, Hauret KG, Canada S, Scott S, Rieger W, Marin R, Jones BH. Increasing the physical fitness of low-fit recruits before basic combat training: An evaluation of fitness, injuries, and training outcomes. Mil Med 171: 45–54, 2006.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

9. Knapik JJ, Grier T, Spiess A, Swedler DI, Hauret KG, Graham B, Yoder J, Jones BH. Injury rates and injury risk factors among Federal Bureau of Investigation new agent trainees. BMC Public Health 11: 920, 2011.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

10. McDaniel LA. A Concept for Functional Fitness, 2006. Available at:http://www.marines.mil/News/Message...-the-usmc-concept-for-functional-fitness.aspx. Accessed January 5, 2015.Cited Here...

11. Milanovic Z, Sporis G, Trajkovic N, James N, Samija K. Effects of a 12 week SAQ training programme on agility with and without the ball among young soccer players. J Sports Sci Med 12: 97–103, 2013.Cited Here...

12. Nindl BC, Williams TJ, Deuster PA, Butler NL, Jones BH. Strategies for optimizing military physical readiness and preventing musculoskeletal injuries in the 21st century. US Army Med Dep J Oct-Dec: 5–23, 2013.Cited Here...

13. Padulo J, Chamari K, Chaabene H, Ruscello B, Maurino L, Sylos Labini P, Migliaccio GM. The effects of one-week training camp on motor skills in Karate kids. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 54: 715–724, 2014.Cited Here... | PubMed

14. Pawlak R, Clasey J, Palmer T, Symons B, Abel MG. The effect of a novel tactical training program on physical fitness and occupational performance in firefighters. J Strength Cond Res 29: 578–588, 2015.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

15. Petersen C. Pre-season tennis conditioning. Can Fam Physician 34: 141–145, 1988.Cited Here... | PubMed

16. Phillips M, Petersen A, Abbiss CR, Netto K, Payne W, Nichols D, Aisbett B. Pack hike test finishing time for Australian firefighters: Pass rates and correlates of performance. Appl Ergon 42: 411–418, 2011.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

17. Random House Inc. Random House Kernerman Webster's College Dictionary. Random House Inc, 2010. Available at: http://www.thefreedictionary.com/athlete. Accessed January 8, 2015.Cited Here...

18. Sell TC, Abt JP, Crawford K, Lovalekar M, Nagai T, Deluzio JB, Smalley BW, McGrail MA, Rowe RS, Cardin S, Lephart SM. Warrior Model for Human Performance and Injury Prevention: Eagle Tactical Athlete Program (ETAP) Part I. J Spec Oper Med 10: 2–21, 2010.Cited Here...

19. Sell TC, Abt JP, Crawford K, Lovalekar M, Nagai T, Deluzio JB, Smalley BW, McGrail MA, Rowe RS, Cardin S, Lephart SM. Warrior Model for Human Performance and Injury Prevention: Eagle Tactical Athlete Program (ETAP) Part II. J Spec Oper Med 10: 22–33, 2010.Cited Here...

20. Smith DL. Firefighter fitness: Improving performance and preventing injuries and fatalities. Curr Sports Med Rep 10: 167–172, 2011.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

21. Sothmann MS, Gebhardt DL, Baker TA, Kastello GM, Sheppard VA. Performance requirements of physically strenuous occupations: Validating minimum standards for muscular strength and endurance. Ergonomics 47: 864–875, 2004.Cited Here... | PubMed | CrossRef

22. Stamford BA, Weltman A, Moffatt RJ, Fulco C. Status of police officers with regard to selected cardio-respiratory and body compositional fitness variables. Med Sci Sports 10: 294–297, 1978.Cited Here... | PubMed

23. Storer TW, Dolezal BA, Abrazado ML, Smith DL, Batalin MA, Tseng CH, Cooper CB. Firefighter health and fitness assessment: A call to action. J Strength Cond Res 28: 661–671, 2014.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

24. Wynn P, Hawdon P. Cardiorespiratory fitness selection standard and occupational outcomes in trainee firefighters. Occup Med (Lond) 62: 123–128, 2012.Cited Here... | View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef