Muscle Insider

New member

“Are calves genetic?”

If you’ve ever seen someone who clearly has never stepped foot in a gym with full, rounded calves, the question has probably crossed your mind; especially if you’ve been hitting your lower legs with calf raises for years with little result. You’ve probably also noticed that some pro bodybuilders, with massive development in every other muscle group, just can’t seem to bring up their calves.

If calf development is genetic, it means those of us who have lucked out in the genetic lottery will never turn our calves into bulls. However, if that’s not true, we’ve still got hope. Let’s dig into the facts to find out.

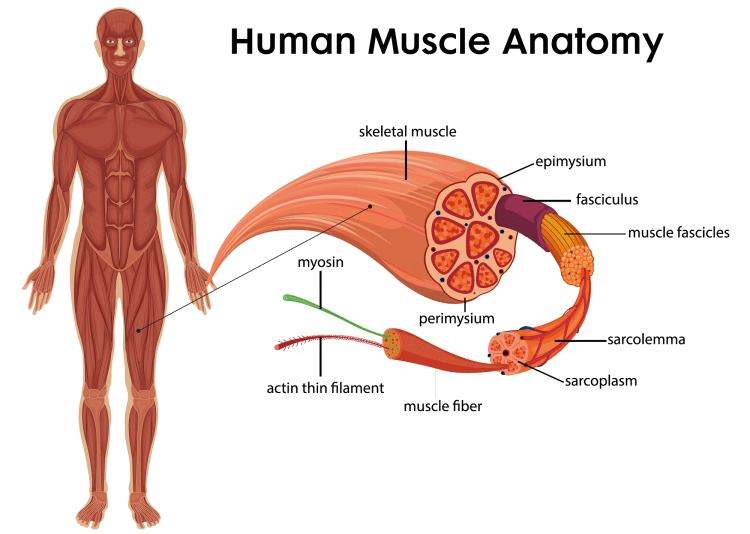

Calf Anatomy

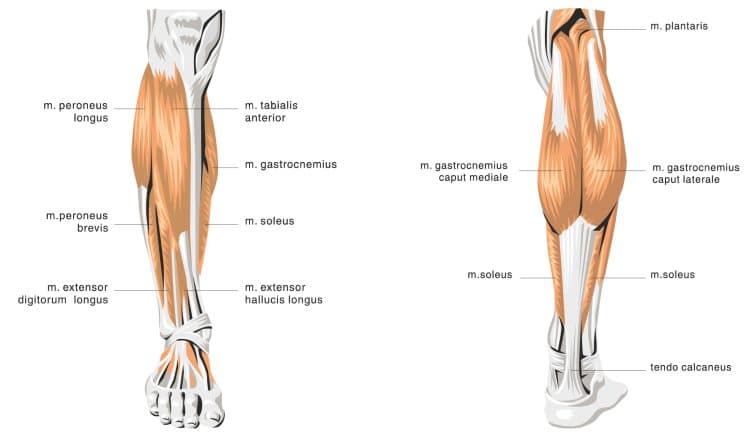

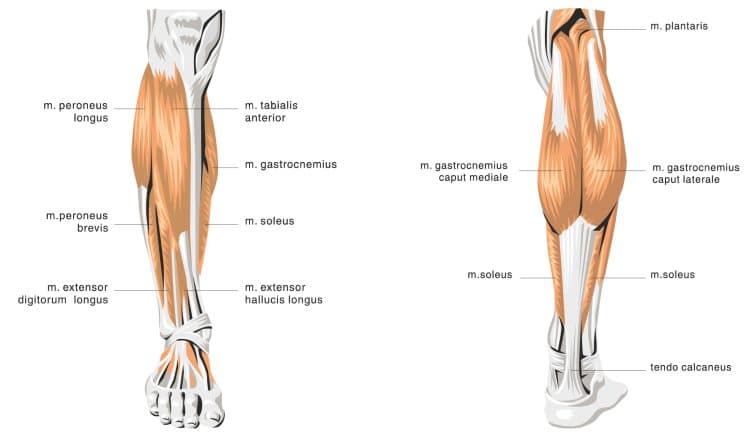

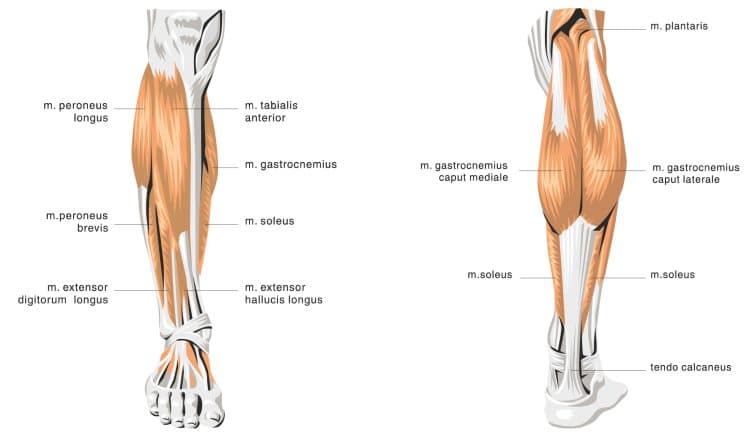

The calves are generally understood to comprise two separate muscles: the gastrocnemius and the soleus. However, some people contend that they are actually two parts of the same muscle. That’s because they both converge at the Achilles tendon and produce the same action; plantar flexion (ankle extension).

The meaty part of the muscle that we generally consider as the calf is the gastrocnemius or gastro. The soleus is a flat muscle that lies under the gastro and has minimal growth potential.

The gastro comprises two parts; the inner and outer head. Both heads originate at the base of the femur, on the medial and lateral condyles (the rounded structure at the end of the bone). These origin points are just above the knee joint.

The soleus originates just below the knee. The gastro and the soleus then converge into the Achilles tendon, which then connects to the heel bone.

Role of Genetics on Calf Development

Genetics does, indeed, have a part to play in your ability to build your calves. Three key genetic factors contribute to the size potential of your lower legs:

Muscle Fiber Type

Muscle Fiber Density

Muscle Belly/Tendon Length

Muscle Fiber Type

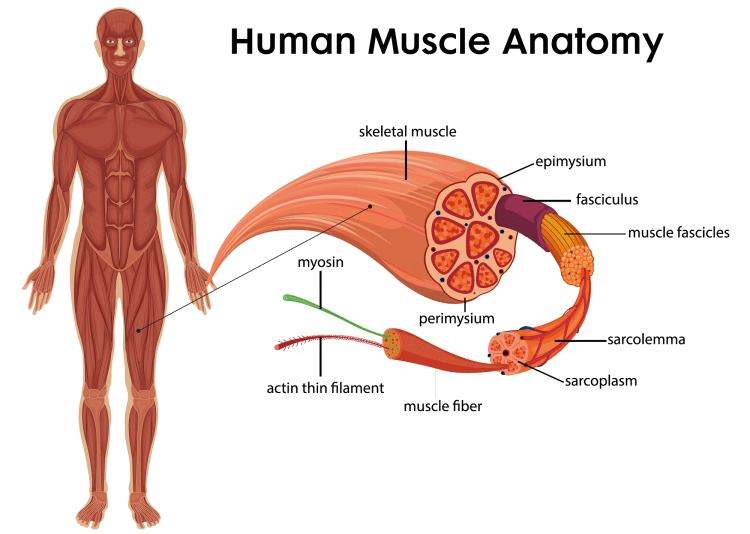

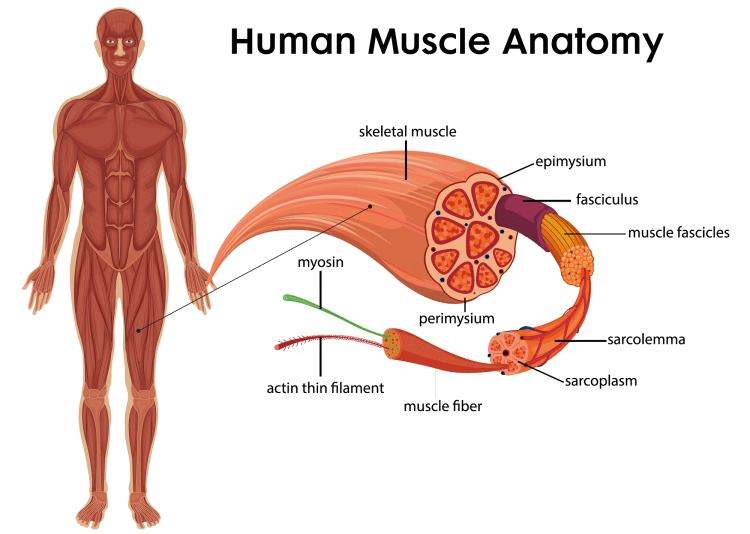

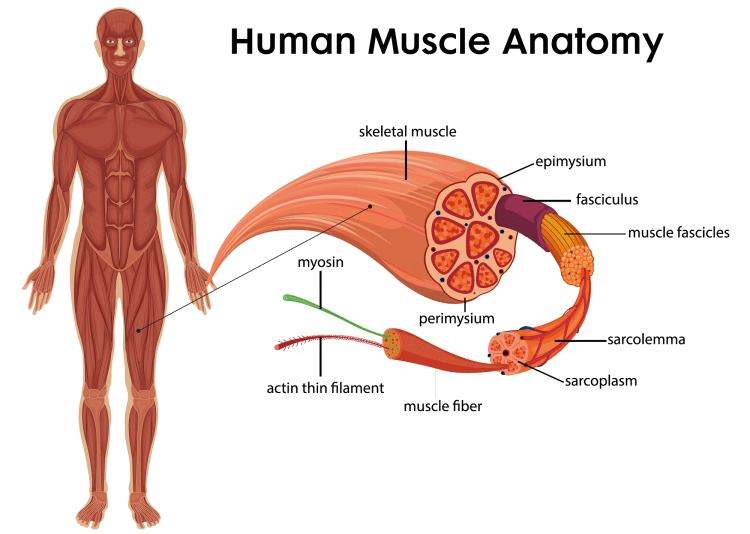

There are two types of muscle fiber; slow twitch (Type I) and fast twitch (Type II). Slow twitch fibers are created for endurance work required for repetitive movements like walking and running. The soleus comprises more fast twitch fibers, while the gastro, though it still has more slow twitch fibers, has a higher percentage of fast twitch fibers. Fast twitch fibers are designed more for explosive, strength-type work, as is required when doing calf raises. These fibers have greater growth potential than slow twitch fibers.

A study by Gollnick et al., published in the European Journal of Physiology, analyzed the muscle fiber make-up of the soleus and gastro and other lower body muscles. They found that, on average, the soleus contained 80% of slow twitch fibers, while the gastro averaged just 57% of fast twitch fibers. [1]

This study also revealed that there is quite a variance in the percentage of fast twitch and slow twitch fibers among the study subjects. The range of fast twitch fibers in the soleus was between 64% and 100%. Regarding the gastro, the range was between 34% and 82%. These differences are the result of the genetic lottery.

So, a person whose gastro comprises 34% fast twitch fibers (and therefore 66% slow twitch fibers) will have a genetic advantage regarding muscle-building potential compared to a person with 82% fast twitch and only 18% slow twitch.

This leads to whether changing your muscle fiber type with training is possible. In other words, could a guy with 82% fast twitch fibers in his calves train a certain way to reduce that down to 50% to have more slow twitch fibers?

The short answer is that researchers don’t know. There is debate among scientists on this question, with some believing that you’re stuck with what you were born with, while others contend that, by doing more of a specific type of training, you may be able to make up to a 10% change. So, you may have a 10% window to develop more slow twitch muscle fibers by doing a calf raise exercises. You would engage in running, cycling, and other endurance work to develop more fast twitch fibers for endurance.

Related: The Average Calf Size for Men and Women

Muscle Fiber Density

Your muscle fiber density refers to the number of muscle fibers per unit of muscle volume. Your genetics determines this. Some people will be born with more muscle fibers in their calves than others. As a result, they will have more muscle-building material to work with. Their muscles will be able to grow bigger and stronger than a person who is born with fewer muscle fibers in the calves.

There is scientific debate about whether it is possible to grow more muscle fibers. This is known as hyperplasia (contrasted with hypertrophy, which refers to making your existing muscles bigger). The current consensus is that if hyperplasia does occur, it would only be possible to a small degree. [2]

Muscle Belly/Tendon Length

Genetics determines the length of a person’s calf muscle belly. A long muscle belly runs down from the back of the knee at least halfway to the ankle. A short muscle belly sits much higher on the lower leg. The ideal for muscle development is having a long belly and a short Achilles tendon. However, the length of your muscle bellies and tendons is entirely a matter of genetics.

High calf bellies are better suited for endurance exercise. In fact, you will notice that many high-level sprinters, basketball players, and endurance athletes have noticeably high calves. It is believed that their longer Achilles tendon provides for more force production in the way that a longer rubber band would.

It is important to remember that, for most people, their genetic predisposition to building calves will be about the same as for the rest of their bodies. So, you’ll probably have the same proportion of slow-twitch to fast-twitch muscle fibers in all your muscles. The length of your muscle bellies will likely also be proportionate throughout your body.

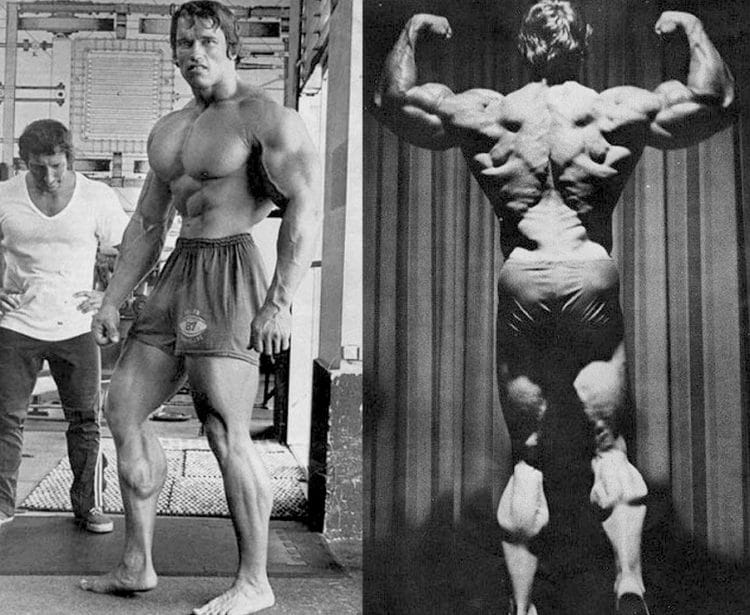

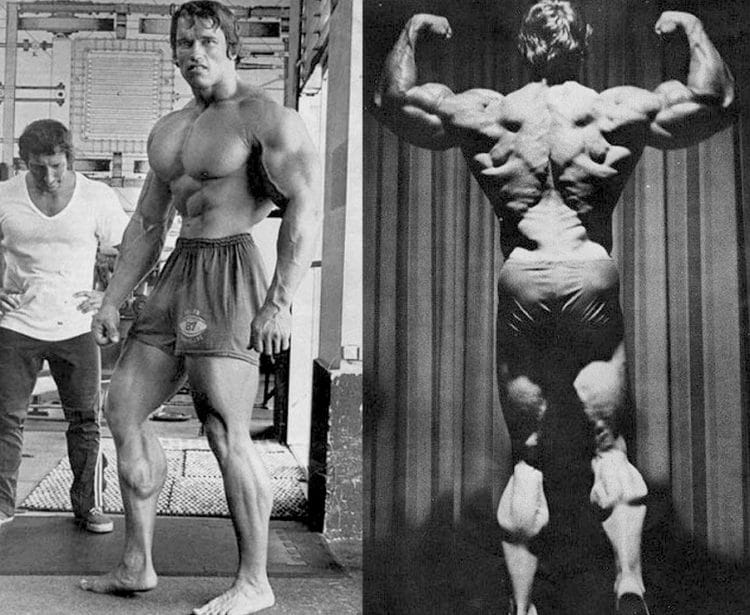

Sometimes, what appears to be a genetic predisposition to weak calves is actually the result of training style and focus. A classic example is when Arnold Schwarzenegger came to America in 1968. Back in Europe, the bodybuilding focus was on the upper body. As a result, Arnold did very little calf work in the gym. Looking at him onstage at the 1968 IFBB Mr. Universe (in which he came second to Frank Zane), you may have concluded that he had terrible calf genetics.

Arnold Schwarzenegger / Instagram

Yet, when Arnold came to appreciate that he needed to seriously focus on his lower legs to start winning competitions, he undertook an amazing transformation. Rather than hiding his weakness, he actually cut all of his training pants off at the knee so that he could be reminded every day of what he needed to focus on. He performed 500-pound sets of standing calf raises, along with seated and donkey calf raises six times per week. Within a few years, during which he once said he invested 5,000 hours on calf training, he was able to turn his biggest weakness into one of his greatest strengths.

Factors Beyond Genetics That Impact Calf Development

So far, we’ve seen that genetic factors affect your calf-building potential. The length, muscle fiber type, and density of your calves will not change much over the course of your life. So, if you’ve got high muscle bellies and long Achilles tendons, there’s nothing you can do about that.

You can’t, for example, alter your calves’ shape by modifying how you do your calf exercises. You may have heard that you can better target the inner or outer head of the gastro by angling your toes in or out when doing calf raises. This is not the case. That’s because the inner and outer heads pull on a single Achilles tendon. This causes the ankle to extend in just one direction. If it were possible for the ‘inner’ calf to work differently from the ‘outer’ calf, each head would require its own separate tendon and separate attachment to the heel bone. That would allow each one to act separately based on toe angling.

So, while you can’t change your calf muscle shape, what you can do is maximize what you’ve been given. Let’s now consider the best way to train to maximize your genetic calf-building potential.

The most commonly seen calf training exercise in the gym is the standing calf raise. This involves placing your shoulders under a pad that is connected to a weight stack. You then place your feet on a block that allows you to lower your heels below your toes level.

I often see people doing this exercise with just their toes on the block. However, this is a limiting foot position that would be akin to doing barbell curls by gripping the bar with only your fingertips.

The best foot position when doing calf raises will provide the most support for the movement to follow. When it’s just your toes on the block, you’ll find those toes slipping off as you progress through your reps, probably resulting in a shortened set.

So, rather than just your toes, you should place the balls of your feet on the block. This is the large, bony pad just below your big toe. Each toe has its own sesamoid bone, running on a diagonal rather than horizontally across the foot. So, to give your foot the most support, you should place the ball of your foot on a slight diagonal from the big toe down to the little toe. This will result in a ‘toes in’ position.

By the way, if you feel your feet slipping off the block while doing a set, you should pause and reset your position. If you don’t, you will compromise your ability to get a full extension and contraction on every rep.

Ideal Range of Motion on Calf Raises

You will never achieve your genetic muscle-building potential unless you move your calves through their full range of motion. Yet, it’s common to see people using an extremely abbreviated range of motion that often equates to a short ‘bouncing’ movement. This usually happens when the person uses more weight than they can properly handle.

The whole reason that you have a block to stand on when doing calf raises is to allow you to get a contraction in the bottom part of the rep. So, if you’re doing reps where your heels don’t even come down to the level of your toes, you’re defeating the purpose of having a block!

It is far better to reduce the weight to achieve a full range of motion.

Knees Straight or Bent During Calf Raises?

If you have completely straight legs (with no knee bend) during the standing calf raise, you might experience some knee discomfort. To avoid this, you should slightly bend your knees throughout the exercise, especially when you start to go heavy. Make sure, though, that you keep your legs locked in this slight knee position to avoid bringing your quads into the movement.

How Much Weight for Calf Raises?

To maximize your calf muscle growth potential, you need to achieve maximum effort on your lower leg workouts. There are two ways you can do this:

Muscle fatigue that results from performing high reps in the 20 to 50 range.

Using a weight that limits you to 80-90% of one rep max, with low reps in the 4-10 range.

The weight you choose for the calf raise, along with every other exercise, should be based on the following parameters:

How many reps do you plan to do

Using a full range of motion

Eliminating momentum

Using proper technique

Maximum effort

Don’t let your ego get in the way when selecting your training resistance. It doesn’t matter what weight your training partner is using; if you cannot tick off each of the criteria listed above, the weight is not right for you.

When it comes to the rep range, the calves require more than the conventional 8-12 rep range for hypertrophy. That’s because of the high slow-twitch fiber makeup of the calves. Slow-twitch fibers are highly resistant to fatigue. As a result, they respond better to higher reps. On the other hand, your fast-twitch fibers require lower reps with heavier weight.

Here is a suggested rep scheme over six sets of calf raises, with the weight increasing on each set:

Set One (Warm-up): 50 reps

Set Two: 30 reps

Set Three: 20 reps

Set Four: 15 reps

Set Five: 10 reps

Set Six: 8 reps

6 Best Calf Exercises

Your gym-based calf training options are quite limited. After all, the calves only do one thing; flex the ankle. So every move must be a variation of the calf raise. These resistance-based exercises will primarily work your fast-twitch muscle fibers. However, there are other things you can do to also work your slow-twitch fibers. By including each exercise in your weekly routine, you will cover all bases:

1. Standing Calf Raise

Steps:

After loading the weight stack, slide under the shoulder pads and grab the handles.

Place your feet on the block, with the balls of your feet and toes pointed slightly inward.

Bend your knees slightly, and then keep your legs locked in that position.

Rise on your toes to complete calf extension.

Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible. Perform your reps in a smooth, fluid manner.

2. 45-Degree Leg Press Calf Raise

Steps:

Load the weight stack and then position yourself in the leg press machine with your lower back firmly against the back pad.

Place the balls of your feet on the base of the footplate.

Fully extend your calves by pushing your toes away from you. Keep your knees supple (slightly bent). Hold for a second.

Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible.

3. Seated Calf Raise

Steps:

Sit on a seated calf raise machine with your thighs tucked under the pads. Set the weights on the machine. Adjust the pad for your height. Place the balls of your feet on the footplate.

Fully extend your calves by raising your heels. Hold for a second.

Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible.

4. Jump Rope

Steps:

Stand with a jump rope in hand; feet shoulder together.

Rotate the wrists to bring the rope overhead.

Jump slightly to allow the rope to travel under your feet.

5. Toe Farmer’s Walk

Steps:

Grab a pair of dumbbells or other heavy objects in your home gym.

Walk up and down your gym floor on your toes until you have walked for 30 seconds.

6. Explosive Box Jumps

Steps:

Stand before a 24-inch high plyometric box. Hinge your hips and swing your arms to load the jump.

Jump both legs onto the box.

Immediately jump down on the other side.

Change direction and repeat.

Wrap-Up

While there is a genetic component to calf training, that doesn’t mean you can’t make the most of what you were blessed with. You can’t change the shape of your calf muscles and can only make minor changes to your muscle fiber type and density. However, you can increase the size of your calf muscle fibers by following a variable resistance workout program across a wide rep range. Besides the conventional gym moves like the standing leg press and seated calf raise, add jumping rope, plyometrics, and the toe farmer’s walk to transform your calves into bulls.

References

Gollnick PD, Sjödin B, Karlsson J, Jansson E, Saltin B. Human soleus muscle: a comparison of fiber composition and enzyme activities with other leg muscles. Pflugers Arch. 1974 Apr 22;348(3):247-55. doi: 10.1007/BF00587415. PMID: 4275915.

MacDougall JD, Sale DG, Alway SE, Sutton JR. Muscle fiber number in biceps brachii in bodybuilders and control subjects. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984 Nov;57(5):1399-403. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.5.1399. PMID: 6520032.

“Are calves genetic?”

If you’ve ever seen someone who clearly has never stepped foot in a gym with full, rounded calves, the question has probably crossed your mind; especially if you’ve been hitting your lower legs with calf raises for years with little result. You’ve probably also noticed that some pro bodybuilders, with massive development in every other muscle group, just can’t seem to bring up their calves.

If calf development is genetic, it means those of us who have lucked out in the genetic lottery will never turn our calves into bulls. However, if that’s not true, we’ve still got hope. Let’s dig into the facts to find out.

Calf Anatomy

The calves are generally understood to comprise two separate muscles: the gastrocnemius and the soleus. However, some people contend that they are actually two parts of the same muscle. That’s because they both converge at the Achilles tendon and produce the same action; plantar flexion (ankle extension).

The meaty part of the muscle that we generally consider as the calf is the gastrocnemius or gastro. The soleus is a flat muscle that lies under the gastro and has minimal growth potential.

The gastro comprises two parts; the inner and outer head. Both heads originate at the base of the femur, on the medial and lateral condyles (the rounded structure at the end of the bone). These origin points are just above the knee joint.

The soleus originates just below the knee. The gastro and the soleus then converge into the Achilles tendon, which then connects to the heel bone.

Role of Genetics on Calf Development

Genetics does, indeed, have a part to play in your ability to build your calves. Three key genetic factors contribute to the size potential of your lower legs:

[*]Muscle Fiber Type

[*]Muscle Fiber Density

[*]Muscle Belly/Tendon Length

Muscle Fiber Type

There are two types of muscle fiber; slow twitch (Type I) and fast twitch (Type II). Slow twitch fibers are created for endurance work required for repetitive movements like walking and running. The soleus comprises more fast twitch fibers, while the gastro, though it still has more slow twitch fibers, has a higher percentage of fast twitch fibers. Fast twitch fibers are designed more for explosive, strength-type work, as is required when doing calf raises. These fibers have greater growth potential than slow twitch fibers.

A study by Gollnick et al., published in the European Journal of Physiology, analyzed the muscle fiber make-up of the soleus and gastro and other lower body muscles. They found that, on average, the soleus contained 80% of slow twitch fibers, while the gastro averaged just 57% of fast twitch fibers. [1]

This study also revealed that there is quite a variance in the percentage of fast twitch and slow twitch fibers among the study subjects. The range of fast twitch fibers in the soleus was between 64% and 100%. Regarding the gastro, the range was between 34% and 82%. These differences are the result of the genetic lottery.

So, a person whose gastro comprises 34% fast twitch fibers (and therefore 66% slow twitch fibers) will have a genetic advantage regarding muscle-building potential compared to a person with 82% fast twitch and only 18% slow twitch.

This leads to whether changing your muscle fiber type with training is possible. In other words, could a guy with 82% fast twitch fibers in his calves train a certain way to reduce that down to 50% to have more slow twitch fibers?

The short answer is that researchers don’t know. There is debate among scientists on this question, with some believing that you’re stuck with what you were born with, while others contend that, by doing more of a specific type of training, you may be able to make up to a 10% change. So, you may have a 10% window to develop more slow twitch muscle fibers by doing a calf raise exercises. You would engage in running, cycling, and other endurance work to develop more fast twitch fibers for endurance.

Related: The Average Calf Size for Men and Women

Muscle Fiber Density

Your muscle fiber density refers to the number of muscle fibers per unit of muscle volume. Your genetics determines this. Some people will be born with more muscle fibers in their calves than others. As a result, they will have more muscle-building material to work with. Their muscles will be able to grow bigger and stronger than a person who is born with fewer muscle fibers in the calves.

There is scientific debate about whether it is possible to grow more muscle fibers. This is known as hyperplasia (contrasted with hypertrophy, which refers to making your existing muscles bigger). The current consensus is that if hyperplasia does occur, it would only be possible to a small degree. [2]

Muscle Belly/Tendon Length

Genetics determines the length of a person’s calf muscle belly. A long muscle belly runs down from the back of the knee at least halfway to the ankle. A short muscle belly sits much higher on the lower leg. The ideal for muscle development is having a long belly and a short Achilles tendon. However, the length of your muscle bellies and tendons is entirely a matter of genetics.

High calf bellies are better suited for endurance exercise. In fact, you will notice that many high-level sprinters, basketball players, and endurance athletes have noticeably high calves. It is believed that their longer Achilles tendon provides for more force production in the way that a longer rubber band would.

It is important to remember that, for most people, their genetic predisposition to building calves will be about the same as for the rest of their bodies. So, you’ll probably have the same proportion of slow-twitch to fast-twitch muscle fibers in all your muscles. The length of your muscle bellies will likely also be proportionate throughout your body.

Sometimes, what appears to be a genetic predisposition to weak calves is actually the result of training style and focus. A classic example is when Arnold Schwarzenegger came to America in 1968. Back in Europe, the bodybuilding focus was on the upper body. As a result, Arnold did very little calf work in the gym. Looking at him onstage at the 1968 IFBB Mr. Universe (in which he came second to Frank Zane), you may have concluded that he had terrible calf genetics.

Arnold Schwarzenegger / Instagram

Arnold Schwarzenegger / Instagram

Yet, when Arnold came to appreciate that he needed to seriously focus on his lower legs to start winning competitions, he undertook an amazing transformation. Rather than hiding his weakness, he actually cut all of his training pants off at the knee so that he could be reminded every day of what he needed to focus on. He performed 500-pound sets of standing calf raises, along with seated and donkey calf raises six times per week. Within a few years, during which he once said he invested 5,000 hours on calf training, he was able to turn his biggest weakness into one of his greatest strengths.

Factors Beyond Genetics That Impact Calf Development

So far, we’ve seen that genetic factors affect your calf-building potential. The length, muscle fiber type, and density of your calves will not change much over the course of your life. So, if you’ve got high muscle bellies and long Achilles tendons, there’s nothing you can do about that.

You can’t, for example, alter your calves’ shape by modifying how you do your calf exercises. You may have heard that you can better target the inner or outer head of the gastro by angling your toes in or out when doing calf raises. This is not the case. That’s because the inner and outer heads pull on a single Achilles tendon. This causes the ankle to extend in just one direction. If it were possible for the ‘inner’ calf to work differently from the ‘outer’ calf, each head would require its own separate tendon and separate attachment to the heel bone. That would allow each one to act separately based on toe angling.

So, while you can’t change your calf muscle shape, what you can do is maximize what you’ve been given. Let’s now consider the best way to train to maximize your genetic calf-building potential.

The most commonly seen calf training exercise in the gym is the standing calf raise. This involves placing your shoulders under a pad that is connected to a weight stack. You then place your feet on a block that allows you to lower your heels below your toes level.

I often see people doing this exercise with just their toes on the block. However, this is a limiting foot position that would be akin to doing barbell curls by gripping the bar with only your fingertips.

The best foot position when doing calf raises will provide the most support for the movement to follow. When it’s just your toes on the block, you’ll find those toes slipping off as you progress through your reps, probably resulting in a shortened set.

So, rather than just your toes, you should place the balls of your feet on the block. This is the large, bony pad just below your big toe. Each toe has its own sesamoid bone, running on a diagonal rather than horizontally across the foot. So, to give your foot the most support, you should place the ball of your foot on a slight diagonal from the big toe down to the little toe. This will result in a ‘toes in’ position.

By the way, if you feel your feet slipping off the block while doing a set, you should pause and reset your position. If you don’t, you will compromise your ability to get a full extension and contraction on every rep.

Ideal Range of Motion on Calf Raises

You will never achieve your genetic muscle-building potential unless you move your calves through their full range of motion. Yet, it’s common to see people using an extremely abbreviated range of motion that often equates to a short ‘bouncing’ movement. This usually happens when the person uses more weight than they can properly handle.

The whole reason that you have a block to stand on when doing calf raises is to allow you to get a contraction in the bottom part of the rep. So, if you’re doing reps where your heels don’t even come down to the level of your toes, you’re defeating the purpose of having a block!

It is far better to reduce the weight to achieve a full range of motion.

Knees Straight or Bent During Calf Raises?

If you have completely straight legs (with no knee bend) during the standing calf raise, you might experience some knee discomfort. To avoid this, you should slightly bend your knees throughout the exercise, especially when you start to go heavy. Make sure, though, that you keep your legs locked in this slight knee position to avoid bringing your quads into the movement.

How Much Weight for Calf Raises?

To maximize your calf muscle growth potential, you need to achieve maximum effort on your lower leg workouts. There are two ways you can do this:

[*]Muscle fatigue that results from performing high reps in the 20 to 50 range.

[*]Using a weight that limits you to 80-90% of one rep max, with low reps in the 4-10 range.

The weight you choose for the calf raise, along with every other exercise, should be based on the following parameters:

When it comes to the rep range, the calves require more than the conventional 8-12 rep range for hypertrophy. That’s because of the high slow-twitch fiber makeup of the calves. Slow-twitch fibers are highly resistant to fatigue. As a result, they respond better to higher reps. On the other hand, your fast-twitch fibers require lower reps with heavier weight.

Here is a suggested rep scheme over six sets of calf raises, with the weight increasing on each set:

Your gym-based calf training options are quite limited. After all, the calves only do one thing; flex the ankle. So every move must be a variation of the calf raise. These resistance-based exercises will primarily work your fast-twitch muscle fibers. However, there are other things you can do to also work your slow-twitch fibers. By including each exercise in your weekly routine, you will cover all bases:

1. Standing Calf Raise

Steps:

[*]After loading the weight stack, slide under the shoulder pads and grab the handles.

[*]Place your feet on the block, with the balls of your feet and toes pointed slightly inward.

[*]Bend your knees slightly, and then keep your legs locked in that position.

[*]Rise on your toes to complete calf extension.

[*]Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible. Perform your reps in a smooth, fluid manner.

2. 45-Degree Leg Press Calf Raise

Steps:

[*]Load the weight stack and then position yourself in the leg press machine with your lower back firmly against the back pad.

[*]Place the balls of your feet on the base of the footplate.

[*]Fully extend your calves by pushing your toes away from you. Keep your knees supple (slightly bent). Hold for a second.

[*]Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible.

3. Seated Calf Raise

Steps:

[*]Sit on a seated calf raise machine with your thighs tucked under the pads. Set the weights on the machine. Adjust the pad for your height. Place the balls of your feet on the footplate.

[*]Fully extend your calves by raising your heels. Hold for a second.

[*]Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible.

4. Jump Rope

Steps:

[*]Stand with a jump rope in hand; feet shoulder together.

[*]Rotate the wrists to bring the rope overhead.

[*]Jump slightly to allow the rope to travel under your feet.

5. Toe Farmer’s Walk

Steps:

[*]Grab a pair of dumbbells or other heavy objects in your home gym.

[*]Walk up and down your gym floor on your toes until you have walked for 30 seconds.

6. Explosive Box Jumps

Steps:

[*]Stand before a 24-inch high plyometric box. Hinge your hips and swing your arms to load the jump.

[*]Jump both legs onto the box.

[*]Immediately jump down on the other side.

[*]Change direction and repeat.

Wrap-Up

While there is a genetic component to calf training, that doesn’t mean you can’t make the most of what you were blessed with. You can’t change the shape of your calf muscles and can only make minor changes to your muscle fiber type and density. However, you can increase the size of your calf muscle fibers by following a variable resistance workout program across a wide rep range. Besides the conventional gym moves like the standing leg press and seated calf raise, add jumping rope, plyometrics, and the toe farmer’s walk to transform your calves into bulls.

References

[*]Gollnick PD, Sjödin B, Karlsson J, Jansson E, Saltin B. Human soleus muscle: a comparison of fiber composition and enzyme activities with other leg muscles. Pflugers Arch. 1974 Apr 22;348(3):247-55. doi: 10.1007/BF00587415. PMID: 4275915.

[*]MacDougall JD, Sale DG, Alway SE, Sutton JR. Muscle fiber number in biceps brachii in bodybuilders and control subjects. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984 Nov;57(5):1399-403. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.5.1399. PMID: 6520032.

Click here to view the article.

If you’ve ever seen someone who clearly has never stepped foot in a gym with full, rounded calves, the question has probably crossed your mind; especially if you’ve been hitting your lower legs with calf raises for years with little result. You’ve probably also noticed that some pro bodybuilders, with massive development in every other muscle group, just can’t seem to bring up their calves.

If calf development is genetic, it means those of us who have lucked out in the genetic lottery will never turn our calves into bulls. However, if that’s not true, we’ve still got hope. Let’s dig into the facts to find out.

Calf Anatomy

The calves are generally understood to comprise two separate muscles: the gastrocnemius and the soleus. However, some people contend that they are actually two parts of the same muscle. That’s because they both converge at the Achilles tendon and produce the same action; plantar flexion (ankle extension).

The meaty part of the muscle that we generally consider as the calf is the gastrocnemius or gastro. The soleus is a flat muscle that lies under the gastro and has minimal growth potential.

The gastro comprises two parts; the inner and outer head. Both heads originate at the base of the femur, on the medial and lateral condyles (the rounded structure at the end of the bone). These origin points are just above the knee joint.

The soleus originates just below the knee. The gastro and the soleus then converge into the Achilles tendon, which then connects to the heel bone.

Role of Genetics on Calf Development

Genetics does, indeed, have a part to play in your ability to build your calves. Three key genetic factors contribute to the size potential of your lower legs:

Muscle Fiber Type

Muscle Fiber Density

Muscle Belly/Tendon Length

Muscle Fiber Type

There are two types of muscle fiber; slow twitch (Type I) and fast twitch (Type II). Slow twitch fibers are created for endurance work required for repetitive movements like walking and running. The soleus comprises more fast twitch fibers, while the gastro, though it still has more slow twitch fibers, has a higher percentage of fast twitch fibers. Fast twitch fibers are designed more for explosive, strength-type work, as is required when doing calf raises. These fibers have greater growth potential than slow twitch fibers.

A study by Gollnick et al., published in the European Journal of Physiology, analyzed the muscle fiber make-up of the soleus and gastro and other lower body muscles. They found that, on average, the soleus contained 80% of slow twitch fibers, while the gastro averaged just 57% of fast twitch fibers. [1]

This study also revealed that there is quite a variance in the percentage of fast twitch and slow twitch fibers among the study subjects. The range of fast twitch fibers in the soleus was between 64% and 100%. Regarding the gastro, the range was between 34% and 82%. These differences are the result of the genetic lottery.

So, a person whose gastro comprises 34% fast twitch fibers (and therefore 66% slow twitch fibers) will have a genetic advantage regarding muscle-building potential compared to a person with 82% fast twitch and only 18% slow twitch.

This leads to whether changing your muscle fiber type with training is possible. In other words, could a guy with 82% fast twitch fibers in his calves train a certain way to reduce that down to 50% to have more slow twitch fibers?

The short answer is that researchers don’t know. There is debate among scientists on this question, with some believing that you’re stuck with what you were born with, while others contend that, by doing more of a specific type of training, you may be able to make up to a 10% change. So, you may have a 10% window to develop more slow twitch muscle fibers by doing a calf raise exercises. You would engage in running, cycling, and other endurance work to develop more fast twitch fibers for endurance.

Related: The Average Calf Size for Men and Women

Muscle Fiber Density

Your muscle fiber density refers to the number of muscle fibers per unit of muscle volume. Your genetics determines this. Some people will be born with more muscle fibers in their calves than others. As a result, they will have more muscle-building material to work with. Their muscles will be able to grow bigger and stronger than a person who is born with fewer muscle fibers in the calves.

There is scientific debate about whether it is possible to grow more muscle fibers. This is known as hyperplasia (contrasted with hypertrophy, which refers to making your existing muscles bigger). The current consensus is that if hyperplasia does occur, it would only be possible to a small degree. [2]

Muscle Belly/Tendon Length

Genetics determines the length of a person’s calf muscle belly. A long muscle belly runs down from the back of the knee at least halfway to the ankle. A short muscle belly sits much higher on the lower leg. The ideal for muscle development is having a long belly and a short Achilles tendon. However, the length of your muscle bellies and tendons is entirely a matter of genetics.

High calf bellies are better suited for endurance exercise. In fact, you will notice that many high-level sprinters, basketball players, and endurance athletes have noticeably high calves. It is believed that their longer Achilles tendon provides for more force production in the way that a longer rubber band would.

It is important to remember that, for most people, their genetic predisposition to building calves will be about the same as for the rest of their bodies. So, you’ll probably have the same proportion of slow-twitch to fast-twitch muscle fibers in all your muscles. The length of your muscle bellies will likely also be proportionate throughout your body.

Sometimes, what appears to be a genetic predisposition to weak calves is actually the result of training style and focus. A classic example is when Arnold Schwarzenegger came to America in 1968. Back in Europe, the bodybuilding focus was on the upper body. As a result, Arnold did very little calf work in the gym. Looking at him onstage at the 1968 IFBB Mr. Universe (in which he came second to Frank Zane), you may have concluded that he had terrible calf genetics.

Arnold Schwarzenegger / Instagram

Yet, when Arnold came to appreciate that he needed to seriously focus on his lower legs to start winning competitions, he undertook an amazing transformation. Rather than hiding his weakness, he actually cut all of his training pants off at the knee so that he could be reminded every day of what he needed to focus on. He performed 500-pound sets of standing calf raises, along with seated and donkey calf raises six times per week. Within a few years, during which he once said he invested 5,000 hours on calf training, he was able to turn his biggest weakness into one of his greatest strengths.

Factors Beyond Genetics That Impact Calf Development

So far, we’ve seen that genetic factors affect your calf-building potential. The length, muscle fiber type, and density of your calves will not change much over the course of your life. So, if you’ve got high muscle bellies and long Achilles tendons, there’s nothing you can do about that.

You can’t, for example, alter your calves’ shape by modifying how you do your calf exercises. You may have heard that you can better target the inner or outer head of the gastro by angling your toes in or out when doing calf raises. This is not the case. That’s because the inner and outer heads pull on a single Achilles tendon. This causes the ankle to extend in just one direction. If it were possible for the ‘inner’ calf to work differently from the ‘outer’ calf, each head would require its own separate tendon and separate attachment to the heel bone. That would allow each one to act separately based on toe angling.

So, while you can’t change your calf muscle shape, what you can do is maximize what you’ve been given. Let’s now consider the best way to train to maximize your genetic calf-building potential.

The most commonly seen calf training exercise in the gym is the standing calf raise. This involves placing your shoulders under a pad that is connected to a weight stack. You then place your feet on a block that allows you to lower your heels below your toes level.

I often see people doing this exercise with just their toes on the block. However, this is a limiting foot position that would be akin to doing barbell curls by gripping the bar with only your fingertips.

The best foot position when doing calf raises will provide the most support for the movement to follow. When it’s just your toes on the block, you’ll find those toes slipping off as you progress through your reps, probably resulting in a shortened set.

So, rather than just your toes, you should place the balls of your feet on the block. This is the large, bony pad just below your big toe. Each toe has its own sesamoid bone, running on a diagonal rather than horizontally across the foot. So, to give your foot the most support, you should place the ball of your foot on a slight diagonal from the big toe down to the little toe. This will result in a ‘toes in’ position.

By the way, if you feel your feet slipping off the block while doing a set, you should pause and reset your position. If you don’t, you will compromise your ability to get a full extension and contraction on every rep.

Ideal Range of Motion on Calf Raises

You will never achieve your genetic muscle-building potential unless you move your calves through their full range of motion. Yet, it’s common to see people using an extremely abbreviated range of motion that often equates to a short ‘bouncing’ movement. This usually happens when the person uses more weight than they can properly handle.

The whole reason that you have a block to stand on when doing calf raises is to allow you to get a contraction in the bottom part of the rep. So, if you’re doing reps where your heels don’t even come down to the level of your toes, you’re defeating the purpose of having a block!

It is far better to reduce the weight to achieve a full range of motion.

Knees Straight or Bent During Calf Raises?

If you have completely straight legs (with no knee bend) during the standing calf raise, you might experience some knee discomfort. To avoid this, you should slightly bend your knees throughout the exercise, especially when you start to go heavy. Make sure, though, that you keep your legs locked in this slight knee position to avoid bringing your quads into the movement.

How Much Weight for Calf Raises?

To maximize your calf muscle growth potential, you need to achieve maximum effort on your lower leg workouts. There are two ways you can do this:

Muscle fatigue that results from performing high reps in the 20 to 50 range.

Using a weight that limits you to 80-90% of one rep max, with low reps in the 4-10 range.

The weight you choose for the calf raise, along with every other exercise, should be based on the following parameters:

How many reps do you plan to do

Using a full range of motion

Eliminating momentum

Using proper technique

Maximum effort

Don’t let your ego get in the way when selecting your training resistance. It doesn’t matter what weight your training partner is using; if you cannot tick off each of the criteria listed above, the weight is not right for you.

When it comes to the rep range, the calves require more than the conventional 8-12 rep range for hypertrophy. That’s because of the high slow-twitch fiber makeup of the calves. Slow-twitch fibers are highly resistant to fatigue. As a result, they respond better to higher reps. On the other hand, your fast-twitch fibers require lower reps with heavier weight.

Here is a suggested rep scheme over six sets of calf raises, with the weight increasing on each set:

Set One (Warm-up): 50 reps

Set Two: 30 reps

Set Three: 20 reps

Set Four: 15 reps

Set Five: 10 reps

Set Six: 8 reps

6 Best Calf Exercises

Your gym-based calf training options are quite limited. After all, the calves only do one thing; flex the ankle. So every move must be a variation of the calf raise. These resistance-based exercises will primarily work your fast-twitch muscle fibers. However, there are other things you can do to also work your slow-twitch fibers. By including each exercise in your weekly routine, you will cover all bases:

1. Standing Calf Raise

Steps:

After loading the weight stack, slide under the shoulder pads and grab the handles.

Place your feet on the block, with the balls of your feet and toes pointed slightly inward.

Bend your knees slightly, and then keep your legs locked in that position.

Rise on your toes to complete calf extension.

Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible. Perform your reps in a smooth, fluid manner.

2. 45-Degree Leg Press Calf Raise

Steps:

Load the weight stack and then position yourself in the leg press machine with your lower back firmly against the back pad.

Place the balls of your feet on the base of the footplate.

Fully extend your calves by pushing your toes away from you. Keep your knees supple (slightly bent). Hold for a second.

Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible.

3. Seated Calf Raise

Steps:

Sit on a seated calf raise machine with your thighs tucked under the pads. Set the weights on the machine. Adjust the pad for your height. Place the balls of your feet on the footplate.

Fully extend your calves by raising your heels. Hold for a second.

Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible.

4. Jump Rope

Steps:

Stand with a jump rope in hand; feet shoulder together.

Rotate the wrists to bring the rope overhead.

Jump slightly to allow the rope to travel under your feet.

5. Toe Farmer’s Walk

Steps:

Grab a pair of dumbbells or other heavy objects in your home gym.

Walk up and down your gym floor on your toes until you have walked for 30 seconds.

6. Explosive Box Jumps

Steps:

Stand before a 24-inch high plyometric box. Hinge your hips and swing your arms to load the jump.

Jump both legs onto the box.

Immediately jump down on the other side.

Change direction and repeat.

Wrap-Up

While there is a genetic component to calf training, that doesn’t mean you can’t make the most of what you were blessed with. You can’t change the shape of your calf muscles and can only make minor changes to your muscle fiber type and density. However, you can increase the size of your calf muscle fibers by following a variable resistance workout program across a wide rep range. Besides the conventional gym moves like the standing leg press and seated calf raise, add jumping rope, plyometrics, and the toe farmer’s walk to transform your calves into bulls.

References

Gollnick PD, Sjödin B, Karlsson J, Jansson E, Saltin B. Human soleus muscle: a comparison of fiber composition and enzyme activities with other leg muscles. Pflugers Arch. 1974 Apr 22;348(3):247-55. doi: 10.1007/BF00587415. PMID: 4275915.

MacDougall JD, Sale DG, Alway SE, Sutton JR. Muscle fiber number in biceps brachii in bodybuilders and control subjects. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984 Nov;57(5):1399-403. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.5.1399. PMID: 6520032.

“Are calves genetic?”

If you’ve ever seen someone who clearly has never stepped foot in a gym with full, rounded calves, the question has probably crossed your mind; especially if you’ve been hitting your lower legs with calf raises for years with little result. You’ve probably also noticed that some pro bodybuilders, with massive development in every other muscle group, just can’t seem to bring up their calves.

If calf development is genetic, it means those of us who have lucked out in the genetic lottery will never turn our calves into bulls. However, if that’s not true, we’ve still got hope. Let’s dig into the facts to find out.

Calf Anatomy

The calves are generally understood to comprise two separate muscles: the gastrocnemius and the soleus. However, some people contend that they are actually two parts of the same muscle. That’s because they both converge at the Achilles tendon and produce the same action; plantar flexion (ankle extension).

The meaty part of the muscle that we generally consider as the calf is the gastrocnemius or gastro. The soleus is a flat muscle that lies under the gastro and has minimal growth potential.

The gastro comprises two parts; the inner and outer head. Both heads originate at the base of the femur, on the medial and lateral condyles (the rounded structure at the end of the bone). These origin points are just above the knee joint.

The soleus originates just below the knee. The gastro and the soleus then converge into the Achilles tendon, which then connects to the heel bone.

Role of Genetics on Calf Development

Genetics does, indeed, have a part to play in your ability to build your calves. Three key genetic factors contribute to the size potential of your lower legs:

[*]Muscle Fiber Type

[*]Muscle Fiber Density

[*]Muscle Belly/Tendon Length

Muscle Fiber Type

There are two types of muscle fiber; slow twitch (Type I) and fast twitch (Type II). Slow twitch fibers are created for endurance work required for repetitive movements like walking and running. The soleus comprises more fast twitch fibers, while the gastro, though it still has more slow twitch fibers, has a higher percentage of fast twitch fibers. Fast twitch fibers are designed more for explosive, strength-type work, as is required when doing calf raises. These fibers have greater growth potential than slow twitch fibers.

A study by Gollnick et al., published in the European Journal of Physiology, analyzed the muscle fiber make-up of the soleus and gastro and other lower body muscles. They found that, on average, the soleus contained 80% of slow twitch fibers, while the gastro averaged just 57% of fast twitch fibers. [1]

This study also revealed that there is quite a variance in the percentage of fast twitch and slow twitch fibers among the study subjects. The range of fast twitch fibers in the soleus was between 64% and 100%. Regarding the gastro, the range was between 34% and 82%. These differences are the result of the genetic lottery.

So, a person whose gastro comprises 34% fast twitch fibers (and therefore 66% slow twitch fibers) will have a genetic advantage regarding muscle-building potential compared to a person with 82% fast twitch and only 18% slow twitch.

This leads to whether changing your muscle fiber type with training is possible. In other words, could a guy with 82% fast twitch fibers in his calves train a certain way to reduce that down to 50% to have more slow twitch fibers?

The short answer is that researchers don’t know. There is debate among scientists on this question, with some believing that you’re stuck with what you were born with, while others contend that, by doing more of a specific type of training, you may be able to make up to a 10% change. So, you may have a 10% window to develop more slow twitch muscle fibers by doing a calf raise exercises. You would engage in running, cycling, and other endurance work to develop more fast twitch fibers for endurance.

Related: The Average Calf Size for Men and Women

Muscle Fiber Density

Your muscle fiber density refers to the number of muscle fibers per unit of muscle volume. Your genetics determines this. Some people will be born with more muscle fibers in their calves than others. As a result, they will have more muscle-building material to work with. Their muscles will be able to grow bigger and stronger than a person who is born with fewer muscle fibers in the calves.

There is scientific debate about whether it is possible to grow more muscle fibers. This is known as hyperplasia (contrasted with hypertrophy, which refers to making your existing muscles bigger). The current consensus is that if hyperplasia does occur, it would only be possible to a small degree. [2]

Muscle Belly/Tendon Length

Genetics determines the length of a person’s calf muscle belly. A long muscle belly runs down from the back of the knee at least halfway to the ankle. A short muscle belly sits much higher on the lower leg. The ideal for muscle development is having a long belly and a short Achilles tendon. However, the length of your muscle bellies and tendons is entirely a matter of genetics.

High calf bellies are better suited for endurance exercise. In fact, you will notice that many high-level sprinters, basketball players, and endurance athletes have noticeably high calves. It is believed that their longer Achilles tendon provides for more force production in the way that a longer rubber band would.

It is important to remember that, for most people, their genetic predisposition to building calves will be about the same as for the rest of their bodies. So, you’ll probably have the same proportion of slow-twitch to fast-twitch muscle fibers in all your muscles. The length of your muscle bellies will likely also be proportionate throughout your body.

Sometimes, what appears to be a genetic predisposition to weak calves is actually the result of training style and focus. A classic example is when Arnold Schwarzenegger came to America in 1968. Back in Europe, the bodybuilding focus was on the upper body. As a result, Arnold did very little calf work in the gym. Looking at him onstage at the 1968 IFBB Mr. Universe (in which he came second to Frank Zane), you may have concluded that he had terrible calf genetics.

Yet, when Arnold came to appreciate that he needed to seriously focus on his lower legs to start winning competitions, he undertook an amazing transformation. Rather than hiding his weakness, he actually cut all of his training pants off at the knee so that he could be reminded every day of what he needed to focus on. He performed 500-pound sets of standing calf raises, along with seated and donkey calf raises six times per week. Within a few years, during which he once said he invested 5,000 hours on calf training, he was able to turn his biggest weakness into one of his greatest strengths.

Factors Beyond Genetics That Impact Calf Development

So far, we’ve seen that genetic factors affect your calf-building potential. The length, muscle fiber type, and density of your calves will not change much over the course of your life. So, if you’ve got high muscle bellies and long Achilles tendons, there’s nothing you can do about that.

You can’t, for example, alter your calves’ shape by modifying how you do your calf exercises. You may have heard that you can better target the inner or outer head of the gastro by angling your toes in or out when doing calf raises. This is not the case. That’s because the inner and outer heads pull on a single Achilles tendon. This causes the ankle to extend in just one direction. If it were possible for the ‘inner’ calf to work differently from the ‘outer’ calf, each head would require its own separate tendon and separate attachment to the heel bone. That would allow each one to act separately based on toe angling.

So, while you can’t change your calf muscle shape, what you can do is maximize what you’ve been given. Let’s now consider the best way to train to maximize your genetic calf-building potential.

The most commonly seen calf training exercise in the gym is the standing calf raise. This involves placing your shoulders under a pad that is connected to a weight stack. You then place your feet on a block that allows you to lower your heels below your toes level.

I often see people doing this exercise with just their toes on the block. However, this is a limiting foot position that would be akin to doing barbell curls by gripping the bar with only your fingertips.

The best foot position when doing calf raises will provide the most support for the movement to follow. When it’s just your toes on the block, you’ll find those toes slipping off as you progress through your reps, probably resulting in a shortened set.

So, rather than just your toes, you should place the balls of your feet on the block. This is the large, bony pad just below your big toe. Each toe has its own sesamoid bone, running on a diagonal rather than horizontally across the foot. So, to give your foot the most support, you should place the ball of your foot on a slight diagonal from the big toe down to the little toe. This will result in a ‘toes in’ position.

By the way, if you feel your feet slipping off the block while doing a set, you should pause and reset your position. If you don’t, you will compromise your ability to get a full extension and contraction on every rep.

Ideal Range of Motion on Calf Raises

You will never achieve your genetic muscle-building potential unless you move your calves through their full range of motion. Yet, it’s common to see people using an extremely abbreviated range of motion that often equates to a short ‘bouncing’ movement. This usually happens when the person uses more weight than they can properly handle.

The whole reason that you have a block to stand on when doing calf raises is to allow you to get a contraction in the bottom part of the rep. So, if you’re doing reps where your heels don’t even come down to the level of your toes, you’re defeating the purpose of having a block!

It is far better to reduce the weight to achieve a full range of motion.

Knees Straight or Bent During Calf Raises?

If you have completely straight legs (with no knee bend) during the standing calf raise, you might experience some knee discomfort. To avoid this, you should slightly bend your knees throughout the exercise, especially when you start to go heavy. Make sure, though, that you keep your legs locked in this slight knee position to avoid bringing your quads into the movement.

How Much Weight for Calf Raises?

To maximize your calf muscle growth potential, you need to achieve maximum effort on your lower leg workouts. There are two ways you can do this:

[*]Muscle fatigue that results from performing high reps in the 20 to 50 range.

[*]Using a weight that limits you to 80-90% of one rep max, with low reps in the 4-10 range.

The weight you choose for the calf raise, along with every other exercise, should be based on the following parameters:

- How many reps do you plan to do

- Using a full range of motion

- Eliminating momentum

- Using proper technique

- Maximum effort

When it comes to the rep range, the calves require more than the conventional 8-12 rep range for hypertrophy. That’s because of the high slow-twitch fiber makeup of the calves. Slow-twitch fibers are highly resistant to fatigue. As a result, they respond better to higher reps. On the other hand, your fast-twitch fibers require lower reps with heavier weight.

Here is a suggested rep scheme over six sets of calf raises, with the weight increasing on each set:

- Set One (Warm-up): 50 reps

- Set Two: 30 reps

- Set Three: 20 reps

- Set Four: 15 reps

- Set Five: 10 reps

- Set Six: 8 reps

Your gym-based calf training options are quite limited. After all, the calves only do one thing; flex the ankle. So every move must be a variation of the calf raise. These resistance-based exercises will primarily work your fast-twitch muscle fibers. However, there are other things you can do to also work your slow-twitch fibers. By including each exercise in your weekly routine, you will cover all bases:

1. Standing Calf Raise

Steps:

[*]After loading the weight stack, slide under the shoulder pads and grab the handles.

[*]Place your feet on the block, with the balls of your feet and toes pointed slightly inward.

[*]Bend your knees slightly, and then keep your legs locked in that position.

[*]Rise on your toes to complete calf extension.

[*]Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible. Perform your reps in a smooth, fluid manner.

2. 45-Degree Leg Press Calf Raise

Steps:

[*]Load the weight stack and then position yourself in the leg press machine with your lower back firmly against the back pad.

[*]Place the balls of your feet on the base of the footplate.

[*]Fully extend your calves by pushing your toes away from you. Keep your knees supple (slightly bent). Hold for a second.

[*]Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible.

3. Seated Calf Raise

Steps:

[*]Sit on a seated calf raise machine with your thighs tucked under the pads. Set the weights on the machine. Adjust the pad for your height. Place the balls of your feet on the footplate.

[*]Fully extend your calves by raising your heels. Hold for a second.

[*]Now lower your heels to below the level of your toes, going down as far as possible.

4. Jump Rope

Steps:

[*]Stand with a jump rope in hand; feet shoulder together.

[*]Rotate the wrists to bring the rope overhead.

[*]Jump slightly to allow the rope to travel under your feet.

5. Toe Farmer’s Walk

Steps:

[*]Grab a pair of dumbbells or other heavy objects in your home gym.

[*]Walk up and down your gym floor on your toes until you have walked for 30 seconds.

6. Explosive Box Jumps

Steps:

[*]Stand before a 24-inch high plyometric box. Hinge your hips and swing your arms to load the jump.

[*]Jump both legs onto the box.

[*]Immediately jump down on the other side.

[*]Change direction and repeat.

Wrap-Up

While there is a genetic component to calf training, that doesn’t mean you can’t make the most of what you were blessed with. You can’t change the shape of your calf muscles and can only make minor changes to your muscle fiber type and density. However, you can increase the size of your calf muscle fibers by following a variable resistance workout program across a wide rep range. Besides the conventional gym moves like the standing leg press and seated calf raise, add jumping rope, plyometrics, and the toe farmer’s walk to transform your calves into bulls.

References

[*]Gollnick PD, Sjödin B, Karlsson J, Jansson E, Saltin B. Human soleus muscle: a comparison of fiber composition and enzyme activities with other leg muscles. Pflugers Arch. 1974 Apr 22;348(3):247-55. doi: 10.1007/BF00587415. PMID: 4275915.

[*]MacDougall JD, Sale DG, Alway SE, Sutton JR. Muscle fiber number in biceps brachii in bodybuilders and control subjects. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984 Nov;57(5):1399-403. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.5.1399. PMID: 6520032.

Click here to view the article.